Blog

-

Conquering Forever Chemicals: U.S. EPA Regulates PFAS in Nation’s Drinking Water

- June 26th, 2024 — by Cheyanne Sharp — Category: Water Quality

- Tweet

-

On April 10, 2024, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) introduced the nation’s first legally enforceable drinking water quality standards to protect against a concerning emerging contaminant, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Press Release, Env't Prot. Agency, Biden-Harris Administration Finalizes First-Ever National Drinking Water Standard to Protect 100M People from PFAS Pollution (Apr. 10, 2024). The rule, a National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (NPDWR), is expected to prevent tens of thousands of illnesses and thousands of deaths by reducing PFAS contamination in public drinking water systems nationwide. PFAS NPDWR, 89 Fed. Reg. 32,532, 32,533 (Apr. 26, 2024) (to be codified at 40 C.F.R. pts. 141–42).

PFAS, often called “forever chemicals,” are a vast group of synthetic chemicals that are notoriously persistent both in the environment and within organisms. PFAS NPDWR Fact Sheet, Env't Prot. Agency. Since the 1940s, they have been used in common products like fire extinguishers, stain- and water-resistant fabrics, nonstick cookware, and even fast food packaging. Our Current Understanding of the Human Health and Environmental Risks of PFAS, Env't Prot. Agency. While PFAS are beneficial for manufacturing, they can be detrimental to human health. Id. PFAS break down slowly, accumulating in our water, soil, air, and food. Id. Scientific studies have revealed that PFAS contamination may lead to health problems such as an increased risk of cancer, a compromised immune system, reproductive harm in pregnant women, and developmental effects in children. Id.

The PFAS NPDWR was issued under the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA), which permits the Administrator of the EPA to promulgate a NPDWR if it is determined that a contaminant (1) may have an adverse effect on human health, (2) is known to occur or substantially likely to occur in public water systems to the extent that it raises a public health concern, and (3) “presents a meaningful opportunity for health risk reduction for persons served by public water systems” if regulated. 42 U.S.C. § 300g-1(b)(1)(A) (1996). Using the “best available” science and public health information as required by the SDWA, along with feedback from 120,000 public comments on its proposed rule, the EPA determined that PFAS regulation was warranted. Id. § 300g-1(b)(3)(A); PFAS NPDWR, 89 Fed. Reg. at 32,537–38.

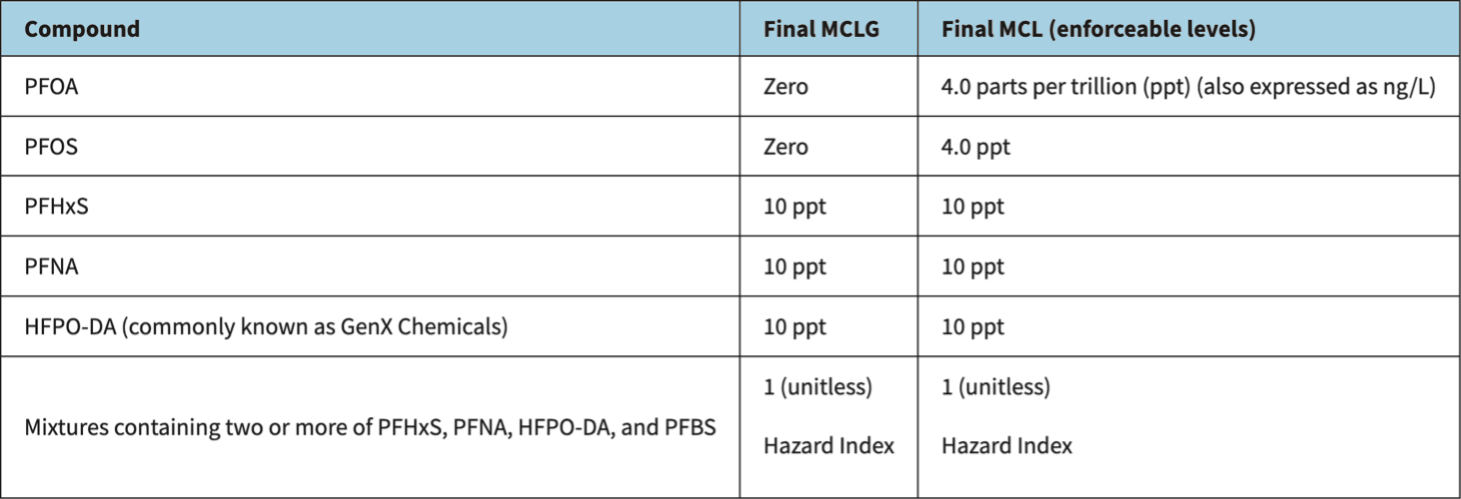

The final rule calls for regulation of five individual PFAS varieties, as well as any mixture of two or more PFAS that commonly combine and amplify the chemicals’ harmful effects. PFAS NPDWR, 89 Fed. Reg. at 32,532. First, the EPA has set health-based, non-enforceable Maximum Contaminant Level Goals (MCLGs) for each substance, which are the levels of contamination required to avoid any known or expected health risks. Id. at 32,563. These goals are accompanied by Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) for each PFAS, which establish the new, legally enforceable limits on the amount of each contaminant permitted in drinking water. Id. at 32,573. The MCLGs signify the EPA’s public health aspirations, and the enforceable MCLs are set as close to those goals as feasible considering the pertinent costs and available treatment solutions. Id.

PFAS NPDWR Fact Sheet, supra, at 1.The MCLs apply to the nation’s public water systems (PWSs), which include any pipe system or other structure that provides the public with water for consumption, as long as the system “has at least fifteen service connections or regularly serves at least twenty-five individuals.” 42 U.S.C. § 300f(4)(A) (2016). The new rule sets out two important timesteps for PWS action. PFAS NPDWR, 89 Fed. Reg. at 32,533. By April 26, 2027, PWSs must complete their initial monitoring for the regulated PFAS and inform the public of contaminant levels in the drinking water. Id. Next, by April 26, 2029, PWSs with PFAS levels exceeding the MCLs must implement solutions to achieve compliance. Id. The rule also calls for ongoing PFAS monitoring, along with public notification and curative measures if future violations arise. Id.

The PFAS NPDWR presents an array of effective and feasible treatment options for PWSs to choose from to reduce PFAS levels, providing flexibility for communities to proceed in a way that works best for them. Id. at 32,624. Some of the best available technologies proposed by the EPA include granular activated carbon, nanofiltration, and reverse osmosis. Id.; Treatment Options for Removing PFAS from Drinking Water, Env't Prot. Agency (Apr. 2024). Monitoring and remediation efforts will be bolstered by the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), the federal government’s largest investment in the nation’s water facilities. PFAS NPDWR, 89 Fed. Reg. at 32,538. Through the BIL, over fifteen billion dollars in funding is available to PWSs through the Drinking Water State Revolving Funds, along with five billion dollars in grants for Emerging Contaminants in Small or Disadvantaged Communities. Id. The EPA is also providing free guidance through its Water Technical Assistance program to help disadvantaged communities identify water challenges, develop action plans, and coordinate funding opportunities. Id.

The EPA expects that six to ten percent of the nation’s PWSs will have to take action to meet the new MCLs, ultimately reducing PFAS exposure for 100 million Americans. Press Release, supra. The PFAS NPDWR is a significant achievement in the EPA’s PFAS Strategic Roadmap, and it also contributes to the Biden Cancer Moonshot goal of halving the rate of cancer-related deaths by 2047. Id. In the meantime, for those concerned about PFAS levels in their own drinking water, the EPA recommends inquiring with local utility providers, checking the EPA’s database of PFAS testing results, and considering home water filters. PFAS NPDWR Fact Sheet, supra.

Although the PFAS NPDWR is a celebrated accomplishment for the Biden-Harris Administration, the final rule is not without its opponents. On June 7, 2024, the American Water Works Association and the Association of Metropolitan Water Agencies challenged the rule as arbitrary and capricious in the United States Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. Am. Water Works Ass’n v. U.S. Env’t Prot. Agency, No. 24-1188 (D.C. Cir. filed June 7, 2024). Concerned about the rule’s potential effects on water affordability, these nonprofit organizations allege that the EPA failed to utilize the best available science and provide the public with a meaningful opportunity to provide their input. Id. The National Association of Manufacturers and the American Chemistry Council filed a comparable suit against the EPA on June 10, 2024, highlighting that the final rule “exceeds the agency’s authority” under the SDWA. Nat’l Ass’n of Mfrs. v. U.S. Env’t Prot. Agency, No. 24-1191 (D.C. Cir. filed June 10, 2024). The PFAS NPDWR is a monumental step toward conquering “forever chemicals” in the United States, but it is only the beginning of an elaborate regulatory journey.

Stay Current with

Our Publications

Subscribe today to our free

quarterly publication, The SandBar

— and to our monthly newsletter,

the Ocean and Coastal Case Alert.

Blog Post Archive

2026

2025

2024

2023

2022

2021

2020

2019

2018

Blog Post Categories

Admiralty Aquaculture

Clean Water Act

COVID-19

Coastal Management

Endangered Species

Environmental Justice

Environmental Law

Fisheries

Flooding

Groundwater

Hurricanes

Insurance

Invasive Species

Litigation Briefs

Marine Debris

Marine Monuments

Miscellaneous

Natural Disasters

Offshore Energy

OSHA

PPP

Seafood

Staff

Torts

Water Quality