February is Black History Month. First proposed by black educators and the Black United Students at Kent State University in 1969, Black History Month is now a federally recognized observance honoring “the too-often neglected accomplishments of black Americans in every endeavor throughout our history.” Pres. Gerald R. Ford, Message on the Observance of Black History Month, February 1976. In addition to celebrating black Americans’ accomplishments, Black History Month also serves as an opportunity for all Americans to educate themselves about the many historical manifestations of racism in the United States (U.S.) that are not typically covered by school curricula. For example, while many are taught about the segregation of drinking fountains, passenger buses, and public schools, few are aware that U.S. beaches were segregated well into the 1960s as well.

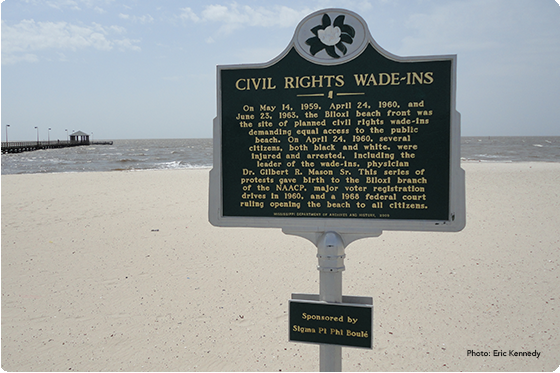

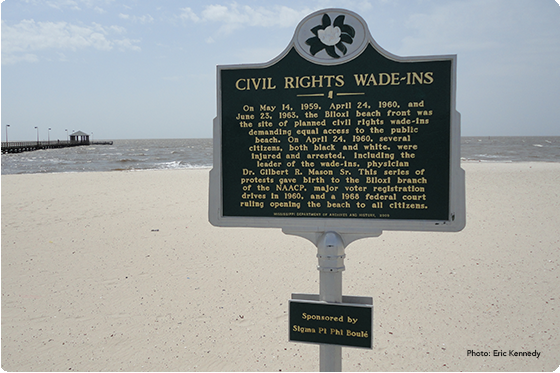

Similar to the lunch counter sit-ins that protested racially segregated restaurants during the Civil Rights Movement, African Americans staged “wade-ins” to protest segregated beaches across the country. In Florida, where Negro Service Council members Lawson Thomas and Ira P. Davis first proposed the idea of wade-ins, nearly two decades of efforts to integrate the state’s beaches culminated in violent attacks on wade-in supporters—including prominent Civil Rights leaders Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and C.T. Vivian—by white mobs in St. Augustine in June 1964. Dr. Gilbert Mason Sr. likewise led a series of wade-ins in Biloxi, Mississippi, where public beaches would not open to all races until 1968.

But this institutionalized injustice was not confined to coastal communities in the Jim Crow South. De jure or de facto segregation was also the norm at beaches Connecticut, Illinois, and California, leading to wade-ins in these states as well. Even in New Jersey, which now protects everyone’s right to beach access under the state’s expansive interpretation of the Public Trust Doctrine, some beaches along Atlantic City’s famous boardwalk were segregated until the mid-1960s. This systemic discrimination, even in places that are now remembered for being relatively enlightened on racial issues for the time, is a stark reminder of why the environmental justice movement would later develop: to amplify voices that are marginalized in decision-making about which communities get a front row seat to the best—and the worst—of nature’s elements.

The legacy and lessons of the wade-ins are as pertinent now as ever. The disproportionate impact of sea level rise, ocean acidification, and other coastal issues on communities of color has led to the recent emergence of marine justice as a topic of interest in academic literature, and marine biologist Dr. Ayana Elizabeth Presley has likewise called for an ocean justice movement to help combat climate change, racism, and gender inequality. On social media, the hashtag #BlackMarineScientist is currently being used to combat stereotypes about African Americans that trace back to segregated beaches by raising the visibility of Black scientists working in marine science. As all communities—especially communities of color —continue to grapple with the climate crisis and other environmental threats, the wade-ins are a sobering reminder of both how far the United States has come and how much more it still needs to accomplish with respect to race and environment.

This Black History Month, the National Sea Grant Law Center remembers and salutes the African Americans who participated in wade-ins to catalyze justice at beaches across the nation. Their bravery and sacrifice are an inspiration to all who champion equality and inclusion, particularly when it comes to the ocean and coastal resources.