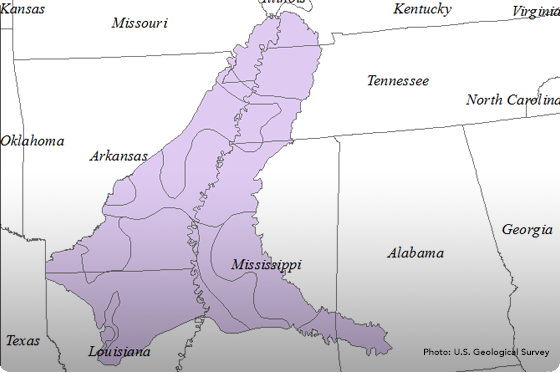

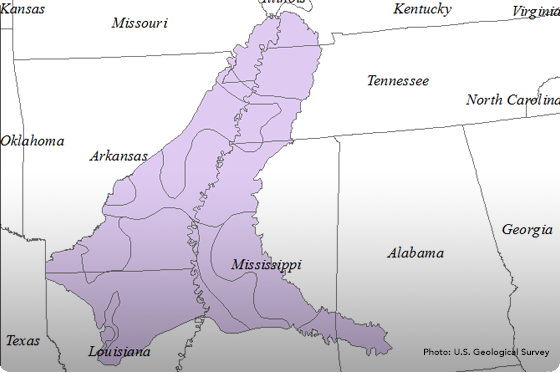

When one state alleges it has suffered a legal harm caused by another state, the complaining state must ask the Supreme Court of the United States–the only court that can hear disputes between states–to hear the case. In 2014, the state of Mississippi asked the Supreme Court if it could file a lawsuit against the state of Tennessee concerning the City of Memphis’s withdrawal of water from a shared aquifer, the Middle Claiborne. Mississippi is concerned with Memphis pumping groundwater close to the border between the two states. Pumping large amounts of groundwater creates “a cone of depression” and changes the flow of water, causing more water to flow towards the well pumping the water. Mississippi claims the city’s pumping has taken billions of gallons of water out of Mississippi, causing it to flow towards Memphis’s wells.

In 2015, the Supreme Court granted Mississippi’s request, allowing the case to go forward. In litigation between states, the Supreme Court serves as a trial court and appoints a Special Master to run a trial-like process. The Special Master hears the parties’ initial motions, evaluates the evidence, and makes findings of fact, conclusions of law, and recommends a decision. The Supreme Court then decides whether or not to follow the Special Master’s recommendation. The Special Master process can take years to complete.

Mississippi v. Tennessee is no exception to the history of lengthy interstate disputes before the Supreme Court. In November 2015, the Supreme Court appointed the Hon. Eugene E. Siler of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit as the Special Master for the case. After considering each state’s initial filings, the Special Master issued a Memorandum of Decision in August 2016 that ordered an initial hearing on whether the aquifer was an interstate resource. In the Memorandum, the Special Master noted that he did not think that Mississippi had made its case in its initial pleadings.

After the 2016 decision by the Special Master, the parties prepared for the initial hearing by gathering their experts, exhibits, and other evidence to support their claims. Tennessee has argued that the aquifer underlies multiple states, making it an interstate resource. Thus, the framework the Supreme Court has developed for interstate surface water should apply to the underground aquifer that both states use. Under that doctrine, known as Equitable Apportionment, neither state has any right to the water until the Supreme Court apportions the water.

Mississippi argues that the water is state property, claiming it owns the groundwater within the state. Thus, Mississippi has not asked for the water to be apportioned through Equitable Apportionment in its lawsuit. Rather, it claims the groundwater within the state is intrastate in nature and has asked for monetary damages of not less than $615 million for the water taken by Memphis.

The initial hearing on whether the aquifer is an interstate resource was originally set to start on January 15, 2019 in Nashville, TN. However, the hearing was delayed until May 20, 2019. The hearing was held for five days from May 20-24, 2019, and both states presented their different theories for the case. In the hearing, Mississippi tried to make the case that the Supreme Court should not “look at the Middle Claiborne Aquifer as a whole” (Mississippi v. Tennessee, No. 143, Original, Report of the Special Master at 17). Rather, Mississippi argues that the subunits in the aquifer should be examined separately: the Memphis Sands in Tennessee and the Sparta Sands in Mississippi. Since the Sparta Sands is a separate geologic formation, Mississippi argued that the groundwater in Mississippi should be treated as intrastate in nature.

After almost a year and a half, the Special Master issued its Report on the hearing on November 5, 2020. In the Report, the Special Master makes two findings. First, the Special Master found that the aquifer is interstate in nature. In making this determination, the Special Master relied on expert testimony and evidence showing the aquifer “is part of a single interconnected hydrological unit underneath multiple states,” and thus, “is an interstate resource” (Report at 11). In doing so, the Special Master rejected Mississippi’s argument that the individual parts of the aquifer should be considered rather than the whole, stating “[b]y definition, an aquifer is nothing but a collection of interconnected units…Mississippi provides no reason to reject this basic understanding of aquifers” (Report at 18). Further, the Special Master noted that the subunits also extend across state boundaries, including the Mississippi-Tennessee border, and the groundwater, though slowly, moves between the two states. Moreover, the fact that groundwater pumping in Memphis affects water levels in Mississippi shows that the aquifer is interstate in nature.

Since the aquifer is interstate in nature, the Special Master’s second finding was that equitable apportionment was the appropriate remedy for Mississippi. The Special Master stated that “[w]hen states fight over interstate water resources, equitable apportionment in the remedy. Mississippi presents no compelling reason to chart a new path for groundwater resources” (Report at 26). Noting that surface water and groundwater have different characteristics, the Special Master noted that equitable apportionment is a flexible doctrine that can “tailor itself to each situation” (Report at 28). Further, the Special Master rejected Mississippi’s contention that it should have the sole authority to govern the taking of water within its borders. While acknowledging that “one state cannot reach into another state to collect water,” the Special Master cited the fact that none of Memphis’s groundwater wells are within Mississippi (Report at 29). As a result, the water dispute must follow the Supreme Court’s precedent and be decided through equitable apportionment.

What are the next steps for the case? First, the Supreme Court must approve the Special Master’s findings or send the case back to him for further proceedings. Traditionally this has meant that the Supreme Court will set a brief schedule, schedule oral arguments, and then issue an opinion, a process that can be lengthy. For instance, in the Florida v. Georgia water dispute, the Special Master in the case issued a Report in December 2019. The Supreme Court set a brief schedule in January 2020, with the briefs meant to allow the parties to argue whether they agree or disagree with the Report. However, while the parties have already filed their briefs, the Supreme Court stated in an October 5, 2020 Order that oral arguments in the case would be scheduled “in due course.”

Second, if the Supreme Court agrees with the Special Master’s findings that the aquifer is an interstate resource that should be subject to equitable apportionment, Mississippi would need to file an amended complaint. This would be required because Mississippi did not seek equitable apportionment in its original complaint, but rather sought monetary damages. If Mississippi chooses not to amend its complaint, the case would be dismissed. For now, though, the case remains up in the air. We will have to wait and see the Supreme Court’s schedule for briefs and oral arguments in the case.