Over the last several years Congress has passed several landmark government spending bills, most notably the Investment Infrastructure and Jobs Act (also known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law), the Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors Act (also known as the CHIPS Act), and the Inflation Reduction Act. Present in each of these bills are a flurry of subsidies, grants, tax cuts, and other spending mechanisms, each of which are tied to a specific government program or agenda designed to improve the lives of the American people in some way or fashion. It can be difficult, however, to properly envision just how the benefit from federal spending authorized in bills like these manifests in various fields and sectors. Who receives the money? Can changes in funding allocations be observed? Data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) National Coastal Resilience Fund Grants awarded from Fiscal Years 2018-2022 illustrate how a large spending bill—in this case, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law—can affect the grant making space.

Introduction: The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Coastal Resilience Fund Grant Program and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law

One of the ways NOAA provides funding to eligible entities is via grants awarded through the National Coastal Resilience Fund (NCRF). Established in 2018, the NCRF “restores, increases and strengthens natural infrastructure to protect coastal communities while also enhancing habitats for fish and wildlife”1. Traditionally, applications are accepted once a year; in 2020 and 2021, they also offered additional emergency grants not considered in this blog. These grants usually require matching funding, although some grantees are exempt from the matching requirement. This grant program experienced a noticeable funding increase in Fiscal Year (FY) 2022, showcasing the impact Congress’s bills have made.

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) provides an opportunity to explore the effect of a single piece of legislation and corresponding federal investments. The BIL was signed on November 15, 2021 and represents a major component of the Biden agenda: a bill designed to improve the quality of American Infrastructure. The bill aims to disburse more than $1.2 trillion over 10 years into roads, highways, airports, resiliency, water, and plenty of other infrastructure needs.2 NOAA will receive nearly $3 billion in funding from FY 2022-2026 for programming that protects the environment and people and addresses climate risks3. The BIL was selected as a case study candidate because the authorized funding began to take effect in FY22 and direct appropriations were provided for NOAA.

Unpacking the National Coastal Resilience Fund: Funding Changes and Accompanying Graphs

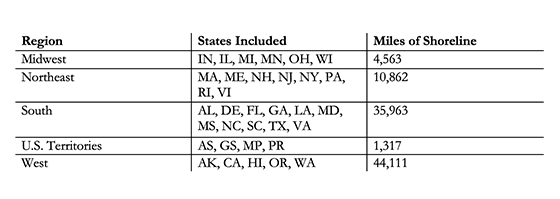

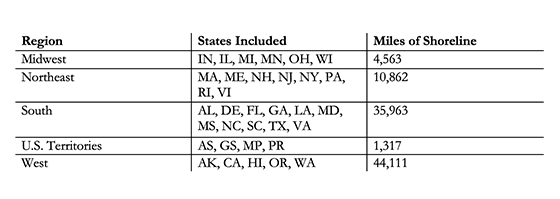

How is the money from the NCRF allocated? The following graphs showcase changes in the grants following BIL passage and where the money goes. Regions are divided according to the divisions the Census Bureau uses, which are shown below.

Figure 1: United States Census Bureau Regions (Landlocked States Excluded)4

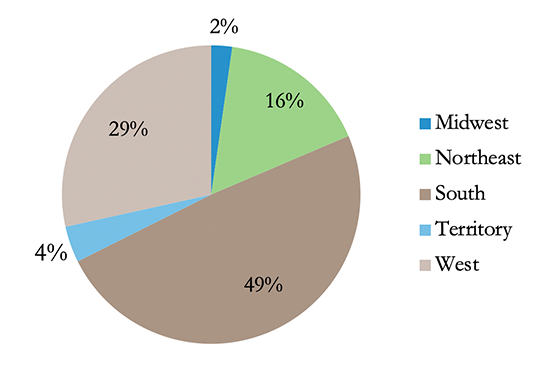

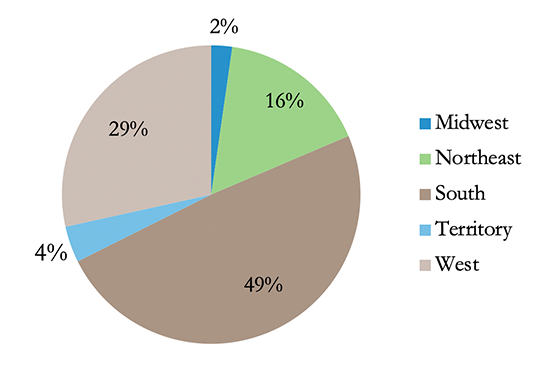

Figure 2: National Coastal Resilience Fund Distribution by Region5

After reviewing the data available for grants awarded by the NCRF since its creation, it is clear the South receives the most funding. [Fig 1.] This is largely in alignment with the number of miles of shoreline: the South as a region has the most states with shorelines and the most miles of shoreline when Alaska’s 33,904 miles of shoreline aren’t considered. It is understandable, then, that U.S. territories would receive as little money as they do—given their size and number relative to the rest of the United States. Similarly, because only a handful of Midwestern states have a shoreline, they also receive a smaller portion of funding.

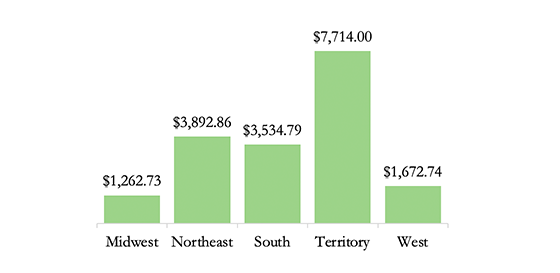

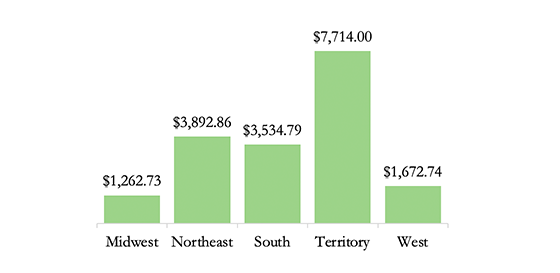

Another way to examine funding allocation is by the amount of funding received per shoreline mile. [Fig. 2]. Under this paradigm, territories receive the most per mile, likely due to high fixed costs infrastructure projects have regardless of size. The biggest surprises, however, are the Northeast and West, who receive higher and lower amounts of money per shoreline, respectively, than one might expect given their shoreline mileage.

Figure 3: National Costal Resilience Fund Money Allocated per Mile of Shoreline6

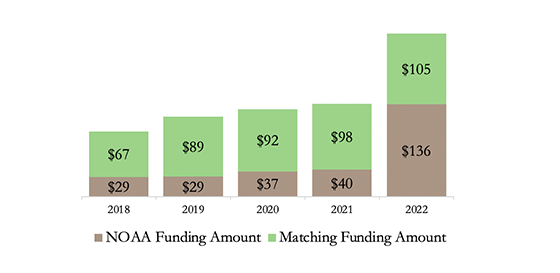

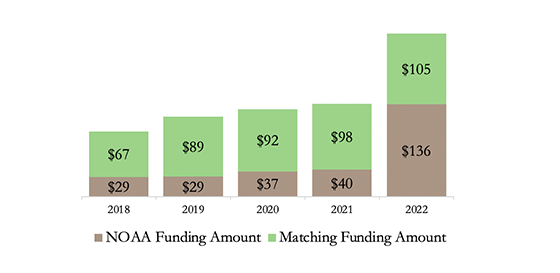

Separate from the distribution conversation, there are significant funding increases post-BIL. As seen in Figure 4, the amount of NOAA funding awarded through the NCRF more than tripled from FY21 to FY22. The Resilience grants also required that less funding be matched with additional support than before. Oftentimes, grants require that the grantee provide evidence that projects are being funded by additional sources than just their own; nearly all NCRF recipients have provided matching funds. That has changed after the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law passage. Whereas before the grants were seen as supplemental—more matching funding was present in FYs 2018-2021 than NOAA funding—matching funding, while increasing overall, decreased in proportion to NCRF funding, marking a clear shift in the grant’s philosophy.

Figure 4: National Coastal Resilience Fund Money Distributed (Millions)7

Why does this matter?

The impacts and distributions of federal funding are often hard to discern. The national conversation surrounding infrastructure packages usually focuses on large, abstract funding totals, like the BIL’s $1.2 trillion. In examining one grant program, the bill’s impact becomes clearer. In just this one case, coastal states received $80 million more funding in FY 22 than in the previous year for climate resilience improvement. This number will likely grow as Inflation Reduction Act funding begins to move out the door. Over the next three years, there will be significantly more money available for coastal resilience projects and organizations that work in this space will have more opportunities to tap into it.

This is especially true for organizations located within a community qualified as “disadvantaged” under the Justice40 directive. Established in Executive Order 14008 issued by President Biden on January 27, 2021, the Justice40 initiative requires that 40% of federal funds be directed to communities designated as “disadvantaged”8. The NOAA, as a federal agency subject to the Executive Order, must implement the NCRF in accordance with this directive. Potential applicants located in such communities may be more attractive grant recipients.

Conclusion

Recent Congressional funding bills have released and will release a swath of accessible funds over the next four years. Grants like the Coastal Resilience Grant from the National Coastal Resilience Fund highlight the expansion in available funds and how the funding is distributed. Taking the time to look at the impacts in bills like the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law make their importance easier to grasp. Tracking funding distribution also ensures that funds are being disseminated in accordance with their overarching directives and achieving their intended effect. Organizations with relevant missions should stay vigilant and take advantage when they can.

1 National Coastal Resilience Fund.

2 The US Bipartisan Infrastructure Law: Breaking it Down.

3 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

4 Geographic Levels Census.gov.

5 Supra note 1.

6 Supra note 1.

7 Supra note 1.

8 Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad Federal Register.