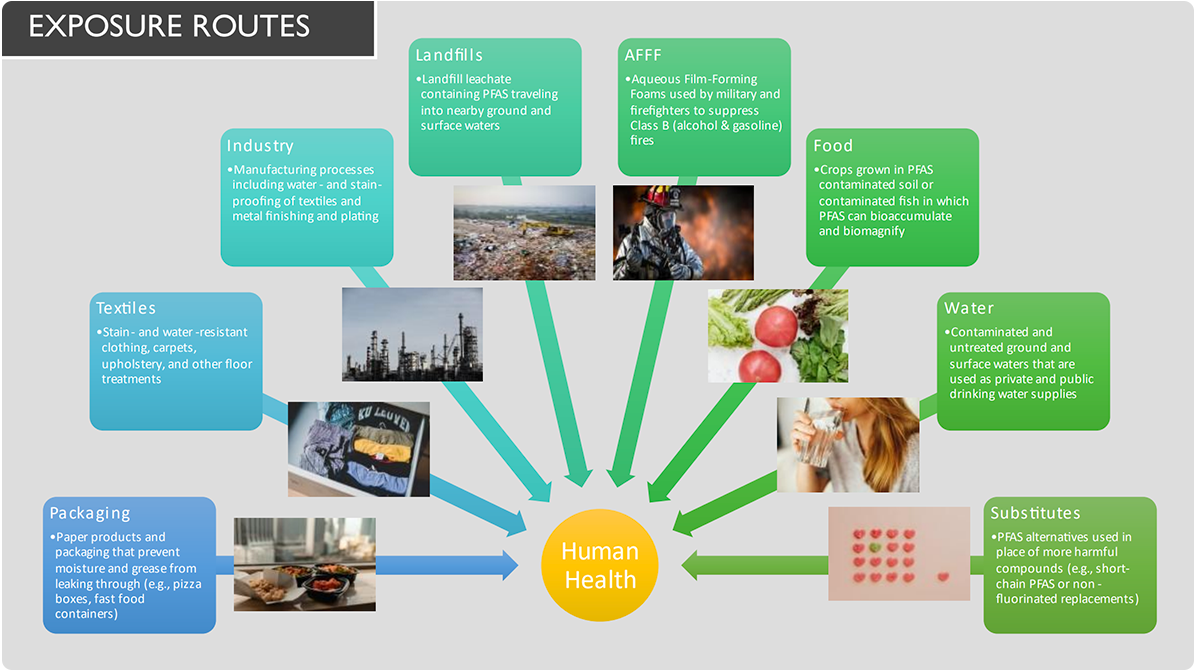

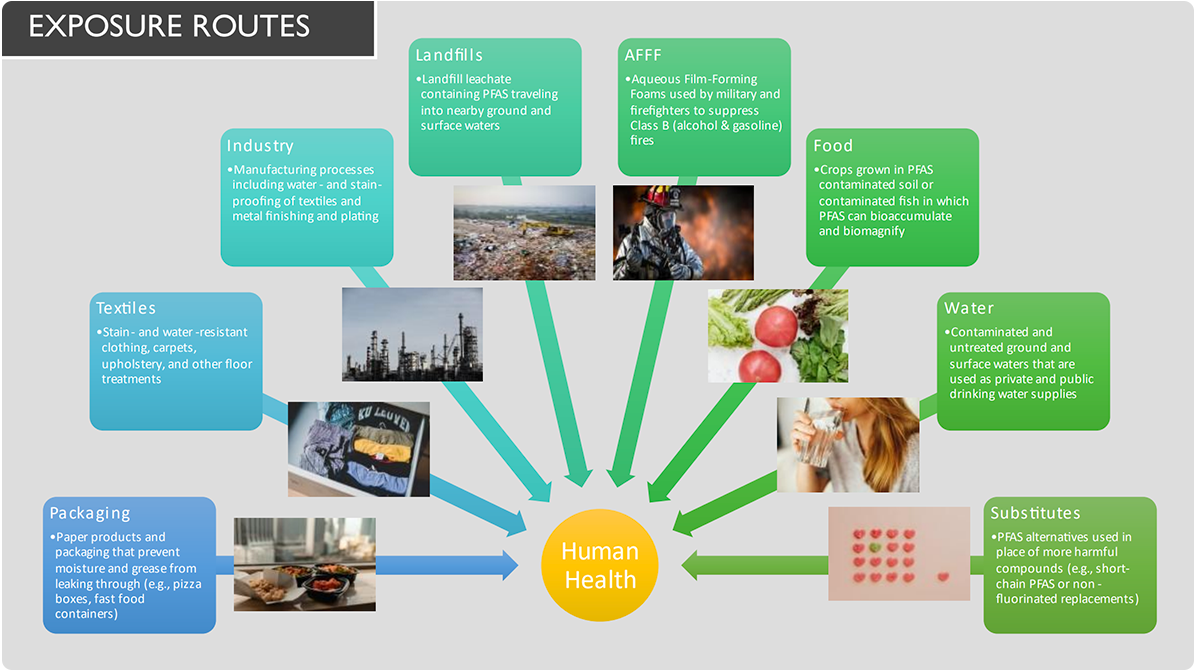

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, are a group of more than 5,000 chemicals that have been used since the 1960s. PFAS are present in a multitude of products across a variety of industries, including nonstick Teflon™ cookware coatings, water-, grease-, and stain-repellents and fire-retardants for clothing, as well as textiles, carpeting, and lining paper products, such as takeout containers. 3M was one of the first companies to use PFAS in their products. In fact, Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) was the primary ingredient in Scotchgard™ fabric and carpet treatment, which is one of 3M’s most popular products. For decades, manufacturing waste containing PFAS from 3M operations was disposed of at 3M sites and the Washington County Landfill in the East Twin Cities Minnesota Metro for decades. This waste then leached into the surrounding environment and groundwater supplies.

PFAS were only identified as chemicals of emerging concern in the early 2000s, when improving analytical methods were able to detect PFAS at lower concentrations than ever before in the environment. These methods also established that these chemicals were not going anywhere. This is because the carbon-fluorine bond, which comprises the chain of the PFAS, is one of the strongest bonds in organic chemistry, which makes the chemical very stable and difficult to break down. Their incredible stability has led to concerns regarding bioaccumulation and biomagnification, earning them the nickname “forever chemicals.”

Interpreting toxicological effects of PFAS is especially difficult due to the sheer number of PFAS in existence. Strategies such as read-across, whereby toxicological effects from one substance can be inferred to be similar to other substances with the same chemical structure and functional groups, can be used to develop toxicological information for PFAS which are lacking data. Common health effects from PFAS exposure include changes in birth weight, decreased fertility, decreased vaccination response and, in the case of PFOA, testicular and kidney cancer. PFAS also have the potential to bioaccumulate in plants and animals, and studies have shown that these exposures are not isolated to specific regions or geographic areas. Instead, they occur worldwide. There are currently no federal regulations under the Safe Drinking Water Act for PFAS, however the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has issued a lifetime health advisory of 15 parts per trillion for both PFOS and PFOA. Regulatory determinations are currently underway for establishing maximum contaminant levels for PFOS and PFOA in drinking water.

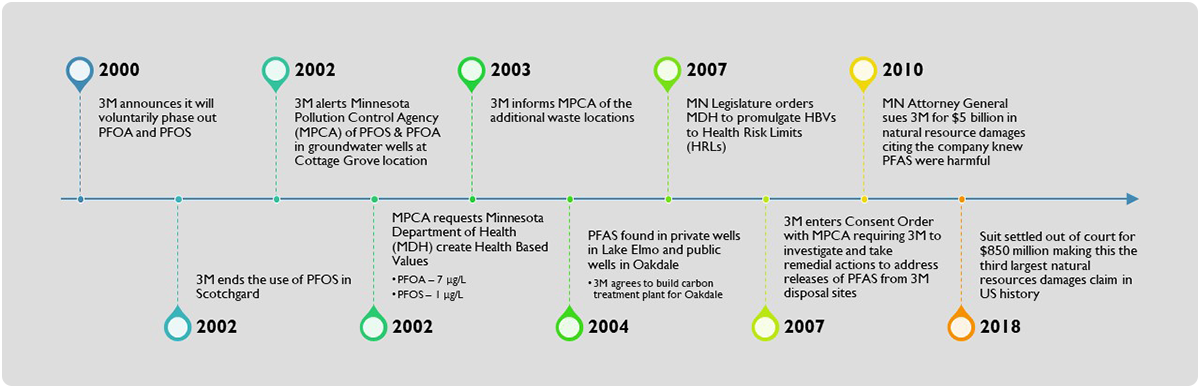

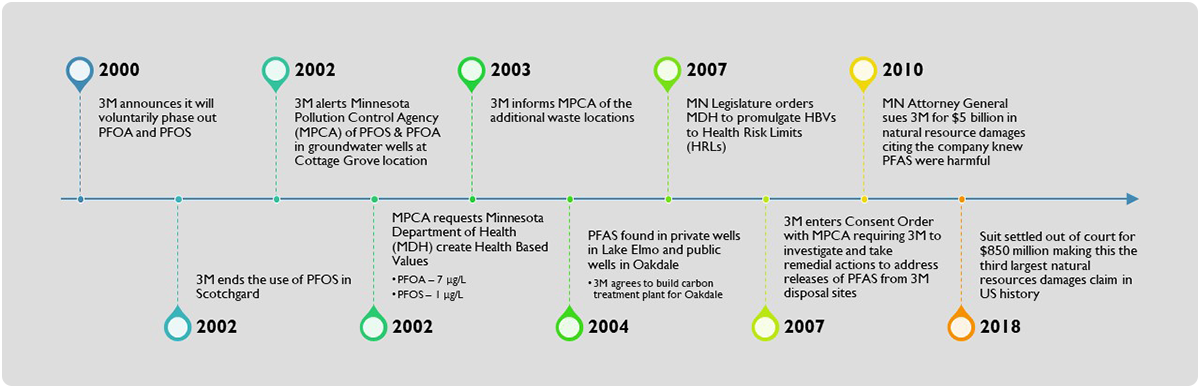

As information regarding the toxicity of PFAS became more widely available, concern regarding the presence of PFAS in drinking water has grown. This concern was amplified by the discovery that 3M knew of the potential toxicity of PFAS for decades, but kept this information from regulators and the public. Then, in 2010, Minnesota Attorney General Lori Swanson sued 3M on behalf of the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR) and Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) for $5 billion in resource damages, specifically claiming that 3M contaminated drinking water in the surrounding area by disposing of waste they knew to be harmful. The suit was eventually settled in 2018 for $850 million and is the third largest environmental damages claim in United States history.

Subtracting legal fees and other expenses, $720 million is available for the DNR and MPCA to use for two priorities: ensuring safe and sustainable drinking water, for which $700 million is allocated, and enhancing natural resources in the East Twin Cities Metro, for which the remaining $20 million will be available. Using work groups comprised of 3M and government representatives, business owners, and members of the affected communities, three plan options for remediation of PFAS contamination of drinking water were developed. Although differing in allocation of funds, each of the plans uses granular activated carbon to treat the existing water supplies, connects new homes to municipal wells, and drills new public and private wells. Additionally, these plans all call for water to be treated to a level that is half what is known to cause health effects, which builds resiliency in the event that future research determines current PFAS health guidance values are too high. The work groups released their three plan options in the fall of 2020 and final determinations by the DNR and MPCA on which option to select are underway. A short timeline summarizing major events in the process can be seen below.

Minnesota’s experience in tackling challenges with unregulated contaminants in drinking water and holding polluters accountable may be an example for other states or communities to emulate and learn from. The successful settlement for natural resource damages sets a precedent for further judicial action for negligent management of potentially harmful waste that can negatively impact public health. High levels of collaboration between community members and leaders, 3M, and state and local governments allowed for greater buy-in to solutions from all stakeholders. Moreover, an open process that allowed questions and concerns from community members to be heard created a level of trust between the community and the decision makers. Although no two scenarios will be the same, the guiding principles of Minnesota’s response to negligent PFAS contamination in drinking water provide an excellent framework for other states and communities to employ.

The full report can be read here: https://ir.library.oregonstate.edu/concern/graduate_projects/kk91ft133.

Cody Bahr completed this report as a capstone project for a Master of Natural Resources degree from Oregon State University under the guidance of Dr. Samuel Chan. Previously, Cody earned a B.S. in Biology from the University of Wisconsin - La Crosse. He currently resides in Minnesota, where he works for the Minnesota Department of Health as a Compliance Officer in the Drinking Water Protection Section administering the Safe Drinking Water Act as it applies to transient noncommunity public water systems.